Japan is entering a period of political uncertainty following an Oct. 27 election where the ruling Liberal Democratic Party and its junior partner lost their majority in parliament for the first time since a vote in 2009. The yen tumbled to a three-month low in the immediate aftermath as investors braced for a weaker administration. A 30-day clock was also set in motion for a new government to emerge, pitting the LDP against the main opposition Constitutional Democratic Party to build a majority, or find a route to a minority government.

What are the key numbers?

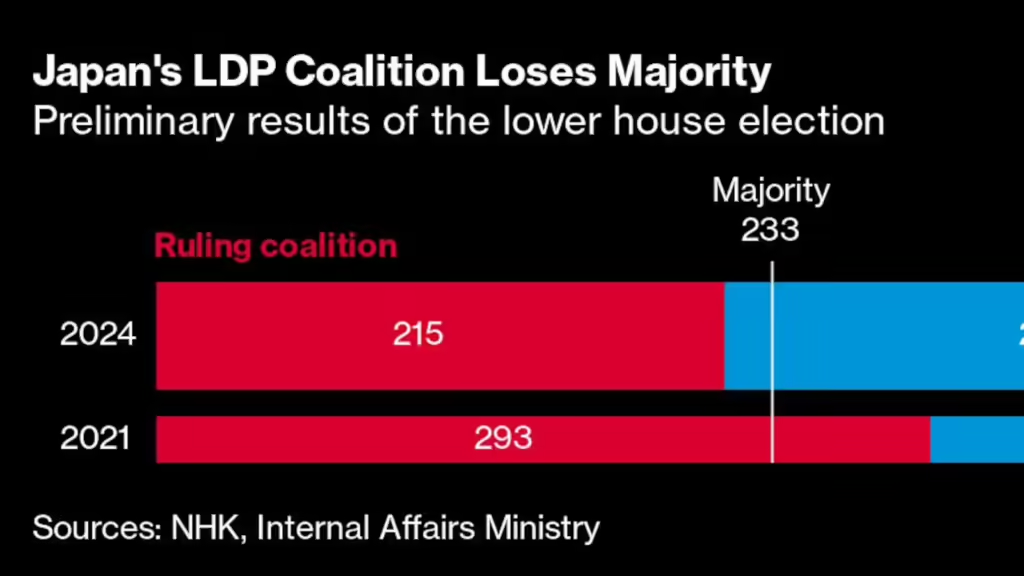

It takes 233 votes in the powerful lower house of parliament to form a government. The center-right LDP and partner Komeito now have 215. The opposition camp and all non-affiliated lawmakers have 250 — with the CDP having the highest tally among that group with 148 seats. The CDP, which bills itself as centrist, has indicated it wants to try to cobble together an unlikely majority coalition among opposition groups that include the Communist Party on the left, and the Japan Innovation Party, or Ishin, a right-leaning party with roots in Osaka politics that favors small government. The LDP could potentially reach a majority with the addition of one of the mid-sized opposition parties.

Who are the kingmakers?

The key players are Ishin, with 38 seats, and the Democratic Party for the People, with 28. The leaders of both parties have dismissed the idea of joining the LDP and Komeito coalition, but the head of the DPP, Yuichiro Tamaki, has shown a willingness to work with the LDP on individual issues.

Both the CDP and the DPP grew out of the Democratic Party of Japan, the only party that has defeated the LDP outright in an election. But there are differences between the camps. For instance, the CDP is seeking for Japan to become carbon neutral by 2050 without reliance on nuclear power, while the DPP wants nuclear plants as part of the energy mix.

Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba is also in a bind over whether to bring back three former lawmakers who lost LDP support after being implicated in a slush fund scandal but managed to win seats independently. Doing so wouldn’t secure him a parliamentary majority and could further damage the LDP’s popularity with another election due next year.

What might be on the table?

CDP leader Yoshihiko Noda, a former prime minister, has said he isn’t interested in a grand coalition and would seek to build a government strong enough to oust the LDP from power.

But in the battle of numbers, Ishiba’s LDP may be able to form a coalition with fewer compromises than Noda. Tamaki’s pet policy of expanding non-taxable income might be a relatively easy lift for Ishiba if it meant staying in power. The Innovation Party, meanwhile, has been looking for a specific change, to turn Osaka into a metropolitan entity without a parallel prefectural structure.

The LDP, which has ruled Japan for all but about four years since its founding in 1955, has shown precedence in offering the post of prime minister to the leader of a smaller party, if it means the LDP can stay in power. About 30 years ago, Socialist party leader Tomiichi Murayama became premier in an LDP-led coalition.

Another possibility is the LDP or CDP leading a minority coalition, with support from other parties on individual policies, although that would likely be the least stable form of government.

How does the process work?

Both houses of parliament must convene within 30 days of a general election to choose a prime minister, according to Japan’s constitution. If nobody gets a majority, a runoff is held between the top two candidates, with the winner taking the top job. The upper house of parliament, currently controlled by the LDP-led coalition, separately picks a prime minister, but the lower house’s decision takes precedence if the two bodies choose different people.

What may happen to Ishiba?

Ishiba took office on Oct. 1 and the LDP may not want to immediately have another leadership election, but his days appear numbered. Even if Ishiba can broker a deal to remain, the bruising at the ballot box would make it harder for him to push ahead with his policy goals, including ramping up funding for regional growth and raising taxes to pay for increased defense spending.

What went wrong for the LDP?

Support for the LDP has ebbed since revelations last year that some party lawmakers were lining their pockets by concealing income generated at fund-raising events. While dozens of LDP politicians were punished by the party and many powerful factions within the group disbanded, opinion polls indicated that voters saw the response as insufficient. On top of this, the strongest inflation in decades squeezed household spending, with surveys indicating that voters didn’t see the LDP as doing enough to fix the problem. The party was also stung by links to the fringe religious group formerly known as the Unification Church.

Source: BNN Bloomberg